THE MACARONI CLUB

We are excited to announce our event “The Macaroni Club” at the DDD, Porto, 27th April 2024! https://www.festivalddd.com/en/current-event/the-macaroni-club/

More infos soon… We’ll keep u updated… For now a sneak peek : )

~~~

WHERE IS THE MACARONI?

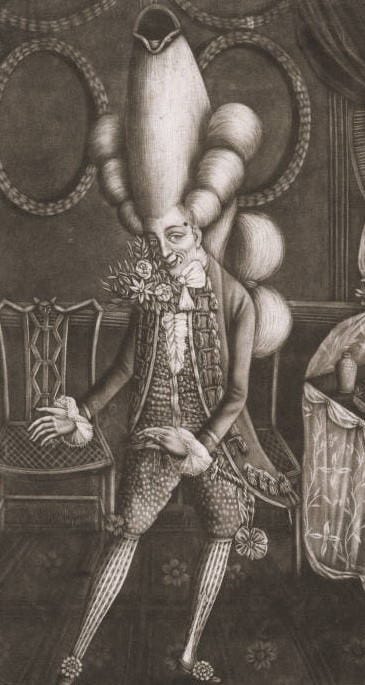

The Macaroni Club might have been a physical place. Suspicions point towards London’s famous assembly-room-styled social club Almack’s, located in King’s Street and founded in 1765. Descriptions by Sir Horace Walpole in some of his letters, very likely refer to the attendees of Almack’s, or the OG-Macaronis: “Macaroni club, which is composed of all the travelled young men who wear long curls and spy-glasses”. Walpole describes fashionable young men, whose aura of folly, waste, fun and oddly characteristic hairstyles, patterned textiles and hanging swords flooded the british Bohemia in the late 18th century.

Their highly aestheticized sense of self, a touch of pretentiousness, their characteristic accent, a deeply effeminate fashion taste and habitual objects like spy-glasses, snuff-boxes and swords were vain, extravagant, attention-grabbing. Macaronis would be distinguished often by their ostentatious hairstyles, full of curls, coiffures and cuts usually associated with feminine silhouettes. Politeness combined with foppery and “affectation”. Reports of gambling losses of thousands of pounds reveal the decadent and careless mindset that permeates the spirit of the macaroni.

The association with Italy (and France) by the British gaze in the late 18th century and thus with fashion and effeminacy partly explains the use of the word “macaroni”. Apart from that, as Lacan says “everyone makes jokes about macaroni, because it is a hole with nothing around it”, an object organised around emptiness (in the words of Peter McNeil).

The Macaroni is presence, the mastering of a (dream of a) post-class technology of glamour, a cultivated spirit filled with social intelligence. This bidimensional surface of social agility, where aesthetics, cosmetics, gesticulation and clothes play an immense role, comes to reveal the artificiality of class, disclosed by the emergence of a rising bourgeoisie this time around.

The Macaroni is a joke, a social extrapolation enabled by the proliferation of caricature as a medium. As the technical conditions for serial print appear, caricature becomes a popular mode of illustration. In the late 18th century, the macaroni lives through the visual satire, in the same way that their patterned clothing and remarkable “clashing aesthetic components" become tightly linked to “masquerade”. Can we detect ourselves in something that was a joke?

The 1771 etching by M. Darly Ridiculous Taste or the Ladies Absurdity became a famous visual satire assigned to the Macaroni figure. It depicts a hairdresser mounting a ladder to trim the voluminous coiffure of a lady, while another man in front of her holds a sextant to measure the hair’s height. This depiction’s captivating nature to the public eye gave way to its artistic reinterpretation onto other mediums, like for instance the famous porcelaine miniature The Coiffure by the Ludwigsburg Porcelain Manufactory. But the cultural boost of the caricature (of the macaroni) reveals something deeper than a reduction of effeminate men to a joke; it shows us how socially constructed meaning is malleable: like the sculpted and trimmed coiffure, it has no limits in its performative articulation, you can always “climb higher”, as long as you’re not afraid to do so; the power tied to class is, beyond wealth, a set of manipulatable social behaviours. Not everyone is born rich and powerful, but everybody can oppose to that premisse by tricking its basic technique.

But is The Macaroni Club a physical place? How much of its atmosphere might be stretched into a trans-historical mood of masculinity-questioning devices?

One century later: many of the points described above might ring a bell: the famous late 19th century dandy. Most notoriously embodied by Oscar Wilde or by Eça de Queiroz’s characters in Os Maias like Carlos da Maia or João da Ega, the dandy, even if through mildly diverging aesthetical devices, embodies the same cultural phenomena of the macaroni. It is not only the effeminate appearance but also the decadence and the rather flamboyant position, which lives in the ambiguity between either opposition or tolerance to nihilism.

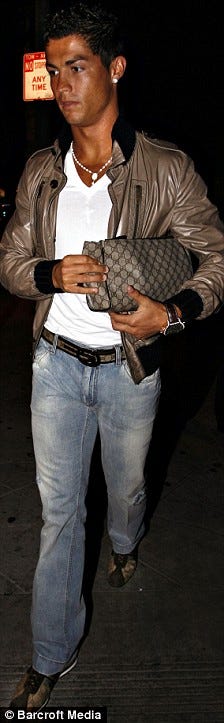

Two centuries later: we won’t deny that depicting effeminate masculinity is not depicting subversion per se. Mark Simpson coins the term “metrosexual” for the first time. He writes in 1994: “It’s been kept underground for too long,” observes one sharply dressed ‘metrosexual’ in his early twenties. He has a perfect complexion and precisely gelled hair and is inspecting a display of costly aftershaves. “This exhibition shows that male vanity’s finally coming out of the closet.”

As y2k late-stage capitalism approaches, the effeminate man is a hopeful attraction to the beauty market. The capitalisation and marketing of male beauty is famously embodied by David Beckham and Cristiano Ronaldo. Ultimately the urban, shaved and glowing, sophisticated man with a sense of physique, hygiene and style is a man that symbolises power and that same symbol has fed capitalism itself. At the same time, how many of you might have been called “metrosexual” in high school — and not with the most flattering tone? Was “metrosexual” not a device to demean deviant masculinities, regardless of “what” they were? What language is the “metrosexual” himself speaking? Or is he pure semantic destruction? And who is the real “metrosexual”? The powerful man or the manhood-failing body?

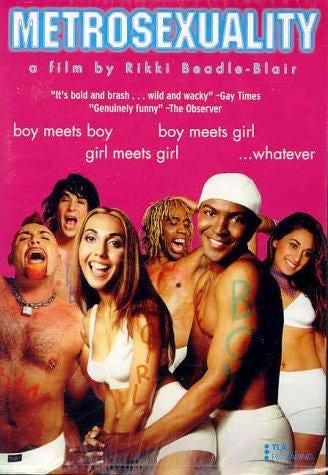

The 2001 TV series Metrosexuality by Nikki Beadle-Blair does not talk solely about effeminate masculinity. Under that name, the story follows as group of people, living happily together as friends, lovers and parents in a world where racism and queerphobia do not exist and the tradicional nuclear family has been dismantled. “Metrosexuality” here refers to a fabric of erotic socio-emocional language that builds something beyond categories. Maybe something laughably idealistic but genuinely revolutionary.

The commentator Philip Bahr describes the extravagant and high-paced humour of the series: “Everyone in the world is part of an urban community that celebrates each person’s unique sexuality, sexual expression, gender expression, gender identity and so on”.

Our proposal is an attempt to temporarily anchor the Macaroni Club here in the Clube Fenianos and inspect the historical fabrics, poked through by the macaronis, observing how their presence revisits the rearticulations of masculinity that characterized the century cusps of the modern era. Collapse is both a fight against and an utilisation of destruction. How far can we go?

A joke book published around 1773 has the following title:

The Macaroni Jester, and Pantheon of Wit; containing all that has lately transpired in the Regions of Politeness, Whim and Novelty; Including A singular Variety of Jests, Witticisms, Bon-Mots, Conundrums, Toasts, Acrostics, & c. - with Epigrams and Epitaphs, of the laughable Kind, and Strokes of Humour hitherto unequalled; which have never appeared in a Book of the Kind