#1 - Stage Magic and Orientalism

A look into Illusionism and the performative techniques of Orientalism in 19th-century England and USA (by Cru Encarnação).

[…] the whole of Empire was a magic trick, a series of individual feats or actions subsumed under an overarching “experience” of colonialism as a panic attack that had to be continually managed. Empire was a complicated performance staged through frauds, disappearances and reappearances, cultural exchanges that involved Orientalism and even a sort of Occidentalism […].

— Mary Lathers, Sleight of Hand: Signor Brunoni, Disappearing Acts, and Empire in Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford.

———

We have been away.

But. The genesis of the assembly has been its divorce from the notion of debt. The assembly refuses to perform the kind of YouTube persona who goes “hey guys, sorry that I didn’t make a video in 4 months. Life has been crazy. I’m back”. No. Firstly, we struggle to see what “us” is and maybe we have committed to the generative curse of that conundrum. Secondly, we have agreed from the beginning that the assembly’s temporality and architecture would be built and maintained according to … contingency, unpredictability, necessity. We knew that someday one meeting might be the last one, if that is how things develop. Maybe? There’s nothing wrong with that. We have trust (maybe too much trust) in our desires, dreams and hopes. Don’t take this as a come-back, but rather as the product of a really long, silent and hidden workshop that some members of the assembly were taking and for which they were considered dead until now.

Our newsletter is a new acquisition to the assembly, which we are initiating as an enzyme: an organic internal and external binding technology. With this newsletter we want references, books, movies, poems, ideas to be shared freely in the assembly. We will write every second week about content we have been connecting with, questioning, destroying, mocking, content that has made us feel alive in some way, even if not for the best reasons. This newsletter can be anything you find interesting for you and the assembly! Any member of the assembly (YOU, who’s reading this) can write a newsletter. Please find a waiting list with instructions for the next newsletters in our link tree.

——

As I have tried to articulate in this lecture, I believe there is a potential in the technicality of stage magic and illusionism to think about performance.

Stage Magic is an incredibly nichified form of entertainment today and it is mostly associated with questionable incel-like masculine aesthetics and a quality of spectacle rather divergent from a piece of performance art, dance, or theatre. However, with a especial peak in the 19th century, stage magic had an immense influence in the cultural sector as one of the main forms of performance. What does this shift of aesthetic value translate about the last century?

Stage magic holds a specific technicality of illusions that can help us think about performance in a more perceptual and less conceptual kind of way, where the interest of the piece lies not only in the central body of the performer, but also in the internal cognitive apparatuses of each member of the audience. How can we think of performance as something that can touch us also through cognitive manipulation and not only through symbolism and concept?

Stage Magic pieces never really have a script or a written form. Therefore their canonisation relies solely on the witnessing of the spectacle by the eye of the tricked audience. Of course there are books explaining how to do certain magic tricks (whose reach did not step into the mainstream until around mid 30s/40s of the 20th century), but single shows/pieces have kept their written format limited to newspapers articles or brief references to these “wonders” or “miracles” in random texts from a third person perspective. If we take stage magic as real performance, how would one write these scripts if what we have left is the layer that masks the sprockets and contraptions of a secret performative technique?

These are all interesting questions that guide our researches. But Alas!

There is certainly a moment when one decides “[breath in] I am going to investigate stage magic”. As a field of knowledge and some kind of rhizome of cultural happenings that has unfolded historically, it represents quite the difficult niche, because its politics and political traditions are questionable and dubious. As researchers aligning with queer theory and rather leftist politics, we tend to often land in publishers, magazines and authors who share similar values, political views and even aesthetics. But what if your field of research was suddenly something like a committee of incels? Reddit meets famous-right-wing-youtube-transsexualism? The 4chan of performance? The twisting spiral of the underground that ends up eating itself alive because it is not able to deal with its demons, anxieties and insecurities?

Well, maybe this is too acute to describe what is at stake or maybe not, but! Since the beginning there have been things that really disturbed us about stage magic — and no, its not only its historically transversal terrible aesthetic choices.

The one we would like to talk about is its intrinsic involvement in and feeding into technologies of Orientalism.

William Ellsworth Robinson, born in 1861 in New York was an engineer working mostly as an assistant for famous magicians. His technical skill and mastery of illusion was impressive, but his charisma rather disappointing. He was awkward and unfortunately not charming enough for a magician. He would always stay behind the stage. Until around the late 1880s when he invented a stage persona called “Chung Ling Soo”, taken directly from the name of Ching Ling Foo, a Chinese magician who gained international fame for notoriously making an enormous bowl of water appear on stage. Long story short: Robinson created this fake chinese persona and advertised himself as “The Greatest Chinese Magician”. Eventually there was a rivalry between Ching Ling Foo and Chung Ling Soo over who was the “Greatest Chinese Magician”. In the end Robinson was able to convince british audiences that he was the one who deserved the title. The authenticity of the Chinese identity here seemed to be anchored not in the origin of the performer (in fact, not for everyone, but for most people it was obvious that Robinson was white, even for the local chinese communities, who curiously never “outed” him), but in the level of engagement each performer would have with the problematic western construction of a universe and a mystique of the “Orient”. Ching Ling Foo, being a chinese man, designed honest performances, without catering to the fetishisation of his own identity in the shape of a so called “self-orientalization”. Robinson, on the other hand, created a whole spectacle and artistic identity ONLY around the racist persona embodying the western’s phantasies of the “Orient”. Be it through mocking or through a fetishisation, the white man has no character without inappropriately relying onto the “Other”.

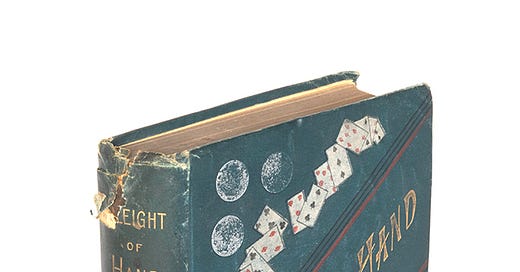

An excerpt from Marie Lathers’ “SLEIGHT OF HAND: SIGNOR BRUNONI, DISAPPEARING ACTS, AND EMPIRE IN ELIZABETH GASKELL’S CRANFORD”:

In 1849, Charles Dickens performed on the Isle of Wight as “The Unparalleled Necromancer Rhia Rhama Rhoos,” a stage name that, for his white guests, readily evoked the stereotypical Indian conjuror. Dickens’s cultural appropriation was apparently the first instance of a British magician performing dressed as an Indian, and his performance was inspired by one he had seen: “The idea to smear his face with boot polish, don a turban and a costume of silken robes, came after seeing Ramo Samee perform […]. An early example of the “Oriental” performing ensemble, the Ramo Samee Juggling Troupe featured acrobatics and juggling as well as a magical act. Ramo Samee was from India, but at least one member of the troupe was European: Khia Khan Khruse, “Chief of the Indian Jugglers,” was in reality Juan Antonio Cruz, a native of Portugal. Dickens’s assumed name was thus a combination of the stage names of an Indian magician and a European impersonating an Indian magician.

Another one of these stories: In 1935, a magician named Arthur Derby, under the assumed name of Karachi, basically claimed that he knew how to perform a trick and that he had learned it from a Gurkha soldier during the Great War. The trick was disputed between the Magic Circle, and the magic community in general: it was called “Indian Rope Trick”. Another long story short: the records of this trick were so dubious and confusing that no one knew anymore if it had really been performed on stage or if it was an invention of the journalist John Elbert Wilkie, who in 1890 wrote an article describing the witnessing of the illusion and then four months later claimed that the article had been an experiment that “had gained far more attention than he had expected”. It spread across Europe, especially in England and France, where many people claimed that they had indeed witnessed this illusion in India. It created a collective hallucination feeding the white imagery about the “mysterious” colonial periphery of the british empire. Did this trick really happen? Did it exist? Once magicians like Derby tried to prove in front of the Magic Circle of London that “they knew” the trick, were they maybe not inventing a new trick based on the viral story? Many like Derby proved their mastery of the trick by emphasizing their proximity to or their personal experience in India. The authenticity of the trick (the one supposedly witnessed by Wilkie) remained unclear and the name “Indian Rope Trick” prevailed. Stories like Dickens’ and Robinson’s racist personas or the phenomenon of the “Indian Rope Trick” all reflect a disturbing connection between the space of an “Other” to our mundane everyday life which we would call “Magic”, the collective construction of the “Orient” and the way both were conjoined metaphysically to fetishise the colonised borders of British Empire.

As Christopher Goto-Jonos investigates, “somewhere between these tendencies in the Golden Age of magic was the space opened up by the aesthetics and politics of Orientalism”. He writes “In the context of the history of magic, it is fascinating to see how the precise period highlighted by [Edward] Said (the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries) was also one in which Western magicians showed a marked interest in representations of the Orient.”

The proliferation of stage magic in the fin-de-siècle was, for many reasons — including for instance 1) the change of setting from the streets to the theatres, 2) the use of technology on stage, and 3) its confluence with the invention of film and photography — an affirmation of modernity; a performative affirmation of modernity.

If modernity is technology, then post-modernity is truth. In that sense, if modernity is highlighting the fin-de-siècle as the foundation for the construction of the Orient, I would claim post-modernity is the further epistemological elaboration of this engagement. Post-modernity cannot be separated from post-truth. And this, in turn cannot be explained without thinking of the 21st century post-9/11 construction of the idea of “terrorism” and it’s epistemologically orchestrated bond with the Middle East.

As we have seen for instance through Adam Curtis’ Hypernormalisation, we cannot think about “post-truth” without thinking about the conspiracy anxiety seeded in US-American society and the way this anxiety was “soothed” and resolved (lol) through the demonisation of the Middle East. If the 19th century is the construction of a “mystique”, a “fantastical” environment that symbolises the magical and mysterious qualities of “oriental” technology as opposed to the engineered occidental ones, then the 20th century is the construction of a monster that symbolises the leaks of information about whatever theory was sold to us to support the presence of coloniality in “post-colonial” times.

These are just some thoughts which deserve further elaboration.

The lies created by the hegemonic forces are both a mixture of fetishisation and demonisation; a process of Othering is a project of distancing and a project of idealisation. “The Orient” is not a place, it is an hallucinatory metaphysical interface, onto which the West has decided to experiment with its own unwanted and unresolved identity problems.

Crispin Sartwell elaborates the idea of “reactionary progressivism”, which means the reapropriation and reinterpretation of something from the past with the intention to generate History forward: “The question is not forward or backward; we’re always moving in both directions at the same time”. He quotes Kierkegaard “The dialectic of repetition is easy, for that which is repeated has been — otherwise it could not be repeated — but the very fact that it has been makes the repetition into something new”. As we think about Stage Magic and Illusionism, our goal must be directed towards the reinterpretation of this form, using its technicalities wisely and not unseeing its highly problematic sides and most importantly, understanding how politics translate into aesthetics in those situations. And one day maybe this cognitive manipulation will not be a way of sedimenting the lies that govern and corrupt us, but as weapons that glitch us out of this hallucination into other possible meanings of what it is to exist collectively.

With that said, we would like to say that we have been trying our best to support our local communities in the fight for liberation of Palestine and would very much encourage you to donate to the following fundraisers:

Don’t forget to boycott, to attend demonstrations, to educate yourself and to involve yourself in legal pressure for ceasefire, collaborate, organize and don’t stop talking about it, make it part of your practice.

~ Cru Encarnação